The New Year started out with several days that were a monochromatic fantasy world of white. Mysterious white-gray fog encased every exposed surface with pure white frost crystals. When the frost fell, the dirty snow and the brown grass got a thin coat of whitewash. And, the falling frost provided a lesson from the Land.

The tops of tall trees seemed to have a more complete covering of frost than the squat wild plum thickets. Don’t worry, I didn’t/couldn’t climb up the big tree to get the artsy shot of white frost against the blue sky. The photo on the right is an enlarged version of one that I took with both feet on solid ground.

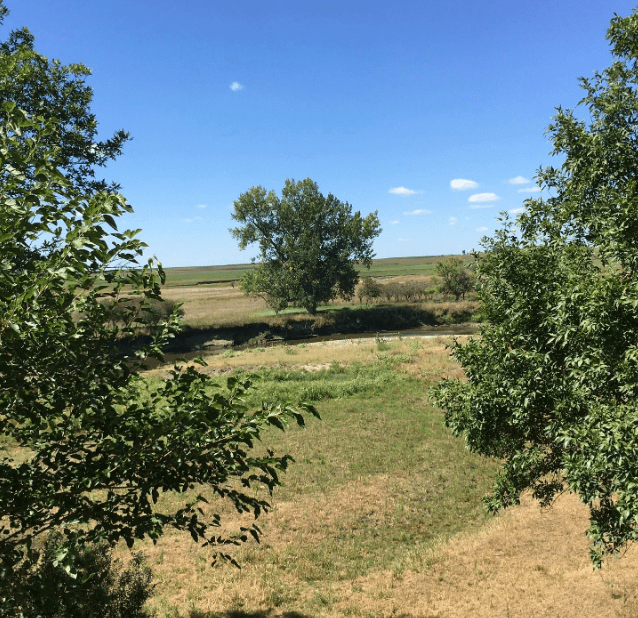

It wasn’t only the trees and plum thickets that got painted white. Every plant that stuck up into the moist air got frosted. These two are along the high bank of the main Creek channel. It’s easy to see why everything was muffled; the insulating frost soaked up all the sound that might be bouncing around.

Fluffy seed heads had more intricate exposed surfaces and so the frost cover was more complete than on the narrow leaves and smooth grass stems. The growth of the frost crystals is due to a phase change of water vapor (which is a gas) to the solid ice crystals. We usually think of ice freezing from water, but the frost formation skips the intermediate step of liquid water and there’s a direction conversion of a gas into a solid.

But, not all exposed surfaces were plant material. Metallic wires didn’t get a coating as thick or as complete as the vegetation. Also when the frost started falling, the wires dropped their white frost first. That’s what produced the line on the ground in the photo on the right.

Although Nature sent a warming breeze that started to dust off everything, even the tall trees, I also shook the frosting from several wires and plants. But, then I suddenly realized what I was doing: I couldn’t resist the urge to exert human control. I should just have trusted and respected Nature’s way of doing things. It was an epiphany for me.

Today is an appropriate day to share this sudden revelation. It is Epiphany which is a day celebrated as a part of the “Twelve days of Christmas” in several Christian traditions. This is supposed to be when the Wise Men brought their gifts. In it’s wisdom, the Land sent a lesson about humility in the white frost. That’s a great way to start the New Year!

If you would like an email notice when these blogs are posted, there is a way to do that: when you’re scrolling through a post, there’s a bar that pops up in the lower right corner, but only if you move up with the scroll. That bar has three dots and if you click the dots, you’ll get the chance to click a “follow” icon.

I know “it ain’t easy”, so I’ll continue to share the link through Face Book. However, it’s not clear when or who gets to see the Face Book notices. But, if you can follow the Word Press procedure, you’ll get an email when I post these “literary gems” on Wednesday afternoons. Thanks.