There’s a growing body of scientific evidence that trees share information, warning their neighbors about danger and nurturing nearby small trees. If you Google “trees communicating” you can get some notion of the traction that this idea is getting. Trees appear to communicate through their root systems and have measurable biochemical reactions to threats of stress. Much of the original work has been done in dense forests like those in the Pacific Northwest, but it may also provide some insights into little trees on the prairie.

This stand of cottonwoods is just down the Creek from our house and you can see it’s distinctive shape from our porch. The tallest and oldest trees tend to be toward the middle and the smaller younger trees are out at the edges. This gives the top of the grove an arch shape—-actually there are two arches shown on this photo. So, are the mature trees near the centers of the clusters providing information, protection, and nurture to the juveniles out around the margins?

Wild plum thickets in our Creek pasture show similar shapes, although the patterns are somewhat harder to see when the individual clusters are close together. The spring blossoms make the thickets look like a single mass. But, if there’s a smaller thicket standing alone you can see the same arched top. The elders toward the centers are providing care for the kids on the outside edges.

Inside the thicket, the trunks of individual plum trees seem to reinforce the pattern. Generally, in the internal tangle of trunks, you see the mature larger trees toward the middle and the immature smaller trees out at the margins. The left photo is a view from the center toward the margin and the right photo is a view from the margin toward the center. These are taken in the fall after the leaves have dropped so you can see the trunks easily. Actually, the individual plants at the margins are more like shrubs or bushes and the individuals in the middle are really only relatively small trees.

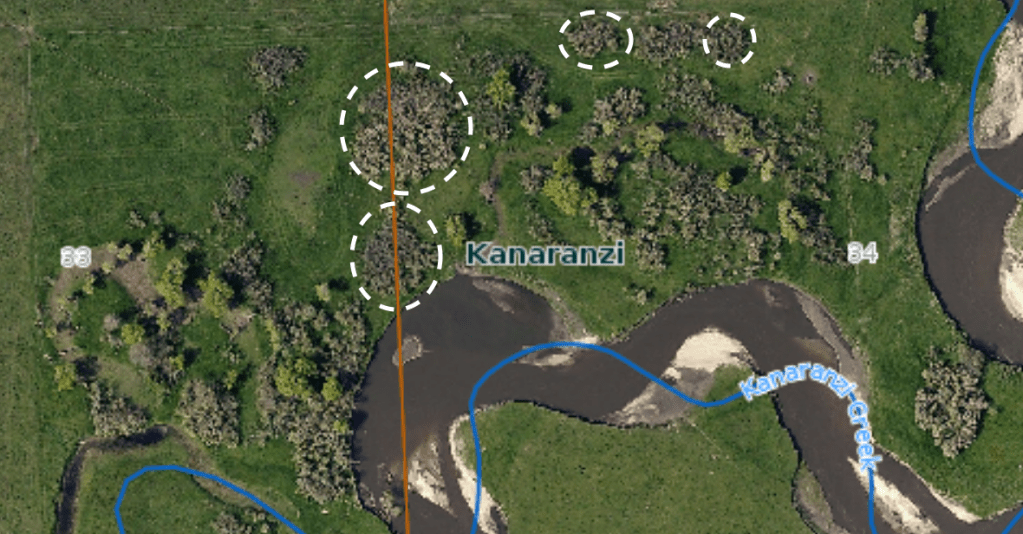

Looking down on the complex overall plum thicket from the perspective of these air photos (available online from Rock County), we can see that it’s actually a cluster of clusters. Single, sub-circular constituent clusters coalesce into a relatively continuous mass that makes it hard to distinguish the outlines of individual clusters. Some of the most obvious ones are circled. But, again a smaller, isolated thicket shows the distinctive sub-circular pattern: mature in the middle and juveniles at the margins. Walking through an isolated thicket, the perspective from “boots on the ground” usually supports the generalization.

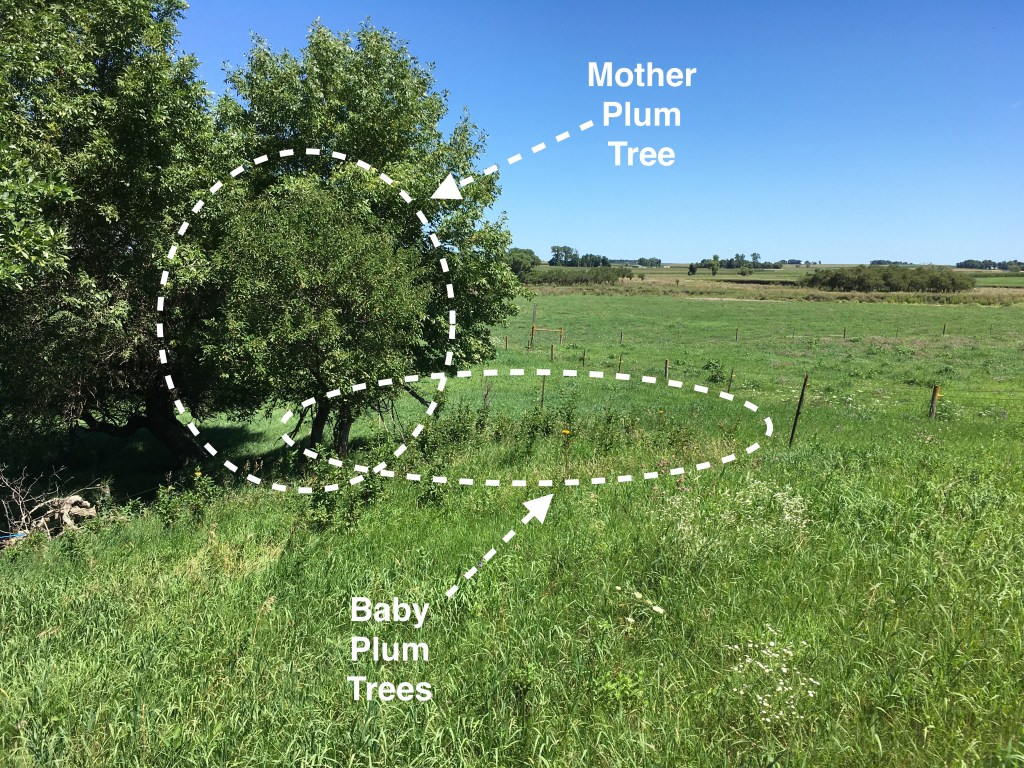

We’ve got an experiment going in one of the paddocks. A single mature tree and her surrounding offspring are fenced off and protected from grazing. If this “exclusion” works and the little ones grow up to make a new thicket, this might be a way to expand the stands of wild plums along the Creek. That would be a good thing because in hot weather the cattle use the shade to get protection from the sun.

Here’s another example of an arched plum thicket, but this one also shows an emerging threat. Increased erosion of the steep channel bank has cut into the plum populations all through the pasture. In fact, the single small tree in the center of this photo is all that remains of a thicket almost completely removed by bank erosion. On a more hopeful note, the cottonwood monarch on the right is probably more safe than it was because the active bank erosion has shifted to the left farther away from the root system.

Although the idea of nurturing mother trees has a certain anthropomorphic appeal, there is an alternative interpretation. Maybe the canopy of the tall older trees cuts sunlight and moisture off from the short ones, so the young ones can only thrive out on the more bare margins. Like so many things in Nature, the reality is probably a dynamic between competition and cooperation (and probably many other variables). But, an over-emphasis on competition has apparently limited our understanding of the important lesson of cooperation among trees until recently. Maybe the mother trees on the prairie can provide some insights into what’s currently going on in the world of humans?

I’m leaning toward the “alternate” explanation … ha!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Trees alter site conditions and therefore are less susceptible to disturbance by fire, grazing or other factors. Conditions like this occur due to a lack of disturbance, exclusion of disturbance, low intensity disturbance or long duration between disturbances. Plum thickets should not be left undisturbed if you want to maintain them. They need to be “renewed” by either high intensity fire top killing them or simply cutting them down in the dormant season. Plum left undisturbed will eventually die out as it ages unless it is burned or cut and allowed to regenerate a new stand.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks. This thicket complex has been at this general location for almost150 years according to the collective memory and our family tradition. Individual thickets have died out in the vicinity and the site has fewer individual “stands”, but the plum thickets still keep coming on. There currently is periodic grazing as a part of our rotational grazing regime, usually in the later summer. Wonder if that’s enough disturbance to maintain regeneration?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wonder how old that stand of plum actually is?? We recently cut down an old and decadent stand of plum for the purpose of regenerating the stand and address other woody encroachment. The stand is regenerating nicely, however is the new regeneration as old as the what was cut down originally?? I’m not sure how to determine this, however I find it to be very interesting how old plants can be. For example, I recently noted a patch of buffalo grass in my backyard that has been there for who knows how long. One thing that I find especially interesting about this stand is that I can find no female plants in the stand. Essentially, the stand has maintained itself via stolons. I wonder if bison chewed on this same stand 200 years ago??

Nice discussion, thanks!!

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for the follow up, Walt. I wonder if anyone has looked at age distributions within a plum thicket or maybe some tree ring counts would give some handle on old at least parts of the thicket are? Your buffalo grass patch is interesting. There’s a school of thought among people working in regenerative agriculture that the ancient seed bank is much more viable than we think. Operators have had native plants “magically” appear under the right grazing regime. But, no female plants implies that your patch didn’t sprout from an old indigenous seed bank? Maybe the buffalo grass has just been waiting to reassert itself when the competition from other plants allows.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Lone Trees | Lone Tree Farm on Kanaranzi Creek

Pingback: Waiting for Plum Blossoms | Lone Tree Farm on Kanaranzi Creek