About ten years ago, a part of a west-facing hill was fenced off (“exclusion”) from the rest of the pasture because it had a remnant prairie with lots of native plants. This year the exclusion was added back into the paddocks because the lack of grazing allowed a thick thatch of old grass to build up. We could have burned it, but it’s a long way from water and I was nervous about trying to control the fire.

The native prairie exclusion was only about 1 acre, but it had almost 40 plant species including 23 forbs (aka “wild flowers”), 11 grasses, and 5 shrubs. Five or six years ago, we had a plant professor (“taxonomist”) from a nearby university tour the site to identify specific species and make the list. He classified the native prairie as “Fair” compared to others that he had seen on the Prairie Coteau in eastern South Dakota and western Minnesota.

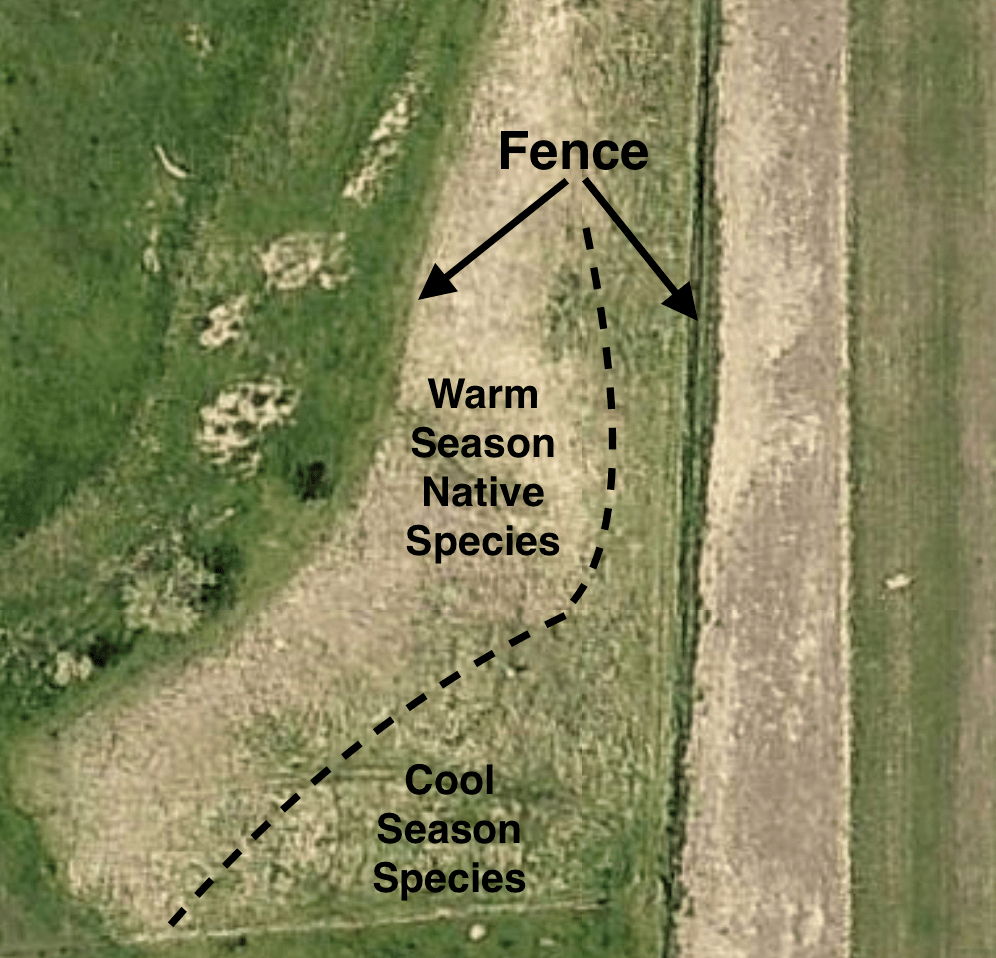

The top of the hill, like most of the Creek pasture, is dominated by brome and blue grass with some clover. It’s great for grazing, but doesn’t have much biodiversity. These cool season grasses get the jump on native plants because they grow rapidly early in the season, but the west slope tends to let the warm season natives do better. The air photo is early in the growing season, so the hill slope is brown with the dry old warm season plants while the hilltop is more green with the cool season new growth. The green area on the left side is the floodplain with a few plum trees and the brown and green strips on the right are in the field on the adjacent hilltop.

The Nature Conservancy is working with prairies of various sizes in Nebraska and the main technical guy has a great blog. He’s really good about balancing the ideal of restoration with the realities of weather and economics. Also, he blurs the distinction between “weeds” and forbs or other non-grass species. In this post he describes how he uses grazing to build biodiversity and also lists some of the plants from their prairies: https://prairieecologist.com/2020/06/29/celebrating-color-movement-and-noise-in-an-evolving-prairie/

These photos show some of the “weeds”/wild flowers that are in both our prairie patch and in his restored prairies. That’s daisy fleabane on the left (with a name like that it must be a weed!) and on the right white Queen Ann’s Lace or wild carrot with purple verbena. There are lots of other great pictures on his post. If you surf back through his other posts you’ll learn that increased biodiversity tends to make a prairie pasture more resilient.

A couple of years ago, I went through the plant list from the prairie hill and picked out half a dozen forbs/wild flowers that had seeds available online. The seeds were planted in a patch west of our house (they’re wild flowers, you know) and some of them really did well. The photo on the left shows either Canada anemone or heath aster as light green low foliage in the foreground; there were cool little white flowers earlier this spring. The middle has some sage, but is mostly brome. And, the tall plants at the back are wild bergamot. There’s also quite a lot of milkweed scattered throughout the picture. It’s the tall plant with the big leaves. The photo on the right is a closer view of the bergamot in bloom.

This spring I tried to do some frost seeding on half dozen areas spread around the Creek pasture. I used a “wet prairie mix” that had 39 different species, although 40% of the mixture was only four grasses. Small seed packets of bergamot and anemone plus leadplant and purple prairie clover were added as “spikes” to the mix. So, the prairie hill gave lessons on what might grow, although the dry hill slope is not the same as the more wet floodplain.

I’m afraid that I’ve got a genetic predisposition to kill thistles, inherited from my father and grandfather. But, they do add to the diversity of the pasture and pollinators like them. Also, the downy seeds are finch food. Another pest that used to bother my family of farmers is milkweed. Yeah, it’s also great for butterflies and other pollinators, but it’s got weed in its name. Still, it doesn’t bother me as much as thistles.

There is a new movement in farming called “regenerative agriculture”. Some of the advocates maintain that the native prairie seeds are preserved naturally in the seed bank of a pasture. The idea is that with the right system of managed grazing, those native plants will come back. In effect, it’s working with Mother Nature rather than buying expensive commercial native prairie seeds that were probably harvested a long way from Kanaranzi Creek.

Thanks George. I’ve forwarded this to some friends up here who are active in prairie restoration, as well as some old classmates that might also find it interesting. Denny

LikeLike

It will be interesting to see if the prairie restoration folks are familiar with the work in Nebraska.

LikeLike

Interesting and I can appreciate some of the “weeds” but I would like to control the brome in areas close to the house and yard.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Tracing Native Prairie | Lone Tree Farm on Kanaranzi Creek